Bereichsnavigation

Olga Adelmann:

Master Violin Maker, Restorer, Scholar

How international collaboration lead to the discovery of forgotten masterpieces

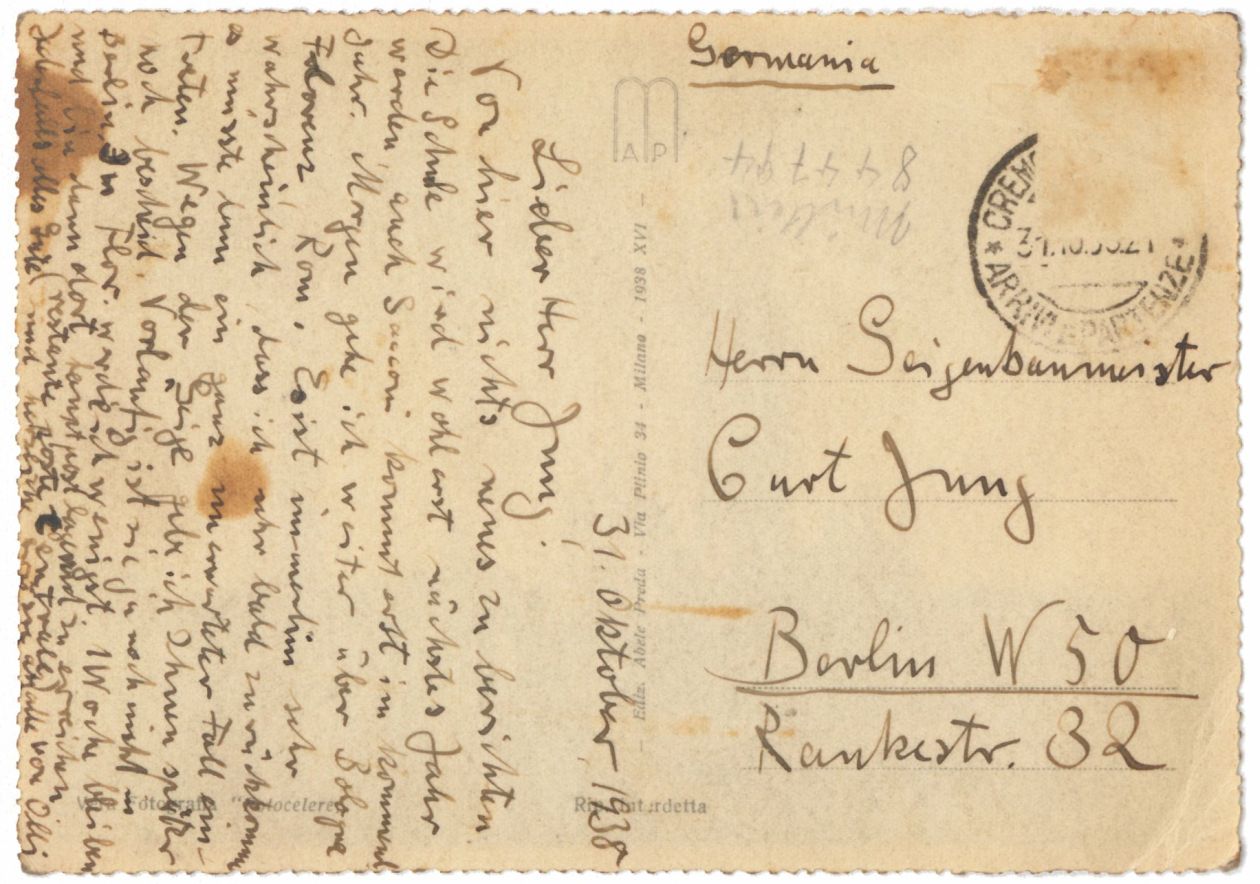

In my personal possession I have an old postcard from the year 1938. The picture side shows a panorama of the city of Cremona with the white marble facade and the iconic Torrazzo. The card is addressed to “Herrn Geigenbaumeister Curt Jung” (Master violinmaker Curt Jung) living on Rankestraße in Berlin, and it is signed with kind regards by “Olli”.

The postcard is a piece of violinmaking history. In the short text, Olga Adelmann, who is to become the first female master* violinmaker (Geigenbaumeisterin) in Germany, tells of the founding of the violinmaking school in Cremona, today's Istituto A. Stradivari. She also mentions Simone Sacconi in passing – probably the most prolific violinmaker, restorer and scholar of the twentieth century, who arrived in Cremona to teach at the school and later wrote one of the most important and influential violinmaking books to date.

This small article attempts to outline the life of Olga, called “Olli”, Adelmann and showcase how her work as a restorer* and researcher* at the Musikinstrumenten-Museum SIMPK and collaboration with violinmakers and scholars worldwide led to the discovery of a previously unknown school of violinmaking.

Olga Adelmann was born on 2 October 1913 in Berlin. She entered her profession by accident, as she recalls in an interview published in the Berliner Illustrierten on 20 January 1938. Shortly before getting her high school diploma, she went to the shop of the master violinmaker Otto Möckel to buy her first own cello. Here, she could watch the master at work. “It was all so new and interesting to me, that I decided in that moment that I too wanted to become a violinmaker.” (Schumann 1938)

As she recalls, Möckel laughed at her at first and tried to talk her out of it. Not only did he tell her about the less-than-ideal prospects of the violinmaking business, but he also doubted her physical abilities to actually do the work. “But I remained strong so that he had to try me out. Yes and then he was astonished.” (Schumann 1938)

Möckel seems to have realised he was wrong about her in the beginning, eventually enabling her to be the first woman in Germany to take the Journeyman exam (Gesellenprüfung) at the violinmakers guild, which she passed.

Otto Möckel himself came from a Berlin-based violinmaking family – his father and brother were both in the same profession. In 1908, he opened up his first shop in Dresden, moving back to Berlin in 1912 after the death of his father. Today, he is known mainly for his book Die Kunst des Geigenbaus (The Art of Violinmaking) from 1930. In the book, he describes not only the process of making violins, but also its repair and that of the bow. There are three aspects of both the book and Möckel himself that seem to have had considerable influence on Olga Adelmann and her work.

The first is the accuracy and precision that Möckel demands for every step of the making process. For example, the method developed by him to form the arching of the back and front plate made it possible to copy historic archings to a high degree of accuracy. Secondly, he saw historical instruments as important sources and models for contemporary violinmaking. For this reason, he composed an extensive archive of measurement data, drawings and photographs of important instruments. Unfortunately, this archive was brought to Silesia for safeguarding during the Second World War and was lost in the aftermath.

Thirdly, because of the important role of historical violins as sources for new ones, he also tried to minimize the loss of original substance during repair work. While this notion is not comparable to the modern idea of conservation, it does show that these old instruments were more to him than just objects whose sole purpose was to make music. (Möckel 1967)

In this context Adelmann learned her craft. The same year she passed the journey mans exam her teacher Otto Möckel died. And in this period the sources are unclear. Möckel's shop was taken over by his employee Curt Jung who later passed down the buisness to his son. According to fembio.org, Olga Adelmann went on a journey to work at different shops.

Though the article in Berliner Illustrierte only mentions a six-week journey to Cremona to see an exhibition in honour of the 200th anniversary of the death of Antonio Stradivari. During this time, she also visited other cities in Italy while spending two weeks travelling to German cities known for their violinmaking traditions:

“… Olli has visited many cities in Italy. And even now she wants to leave, wants to work in different workshops, wants to learn different methods. ‘Maybe it’lll be possible next year.’, she says, ‘one day for sure.’”

It remains unclear from the available sources if this day came and how exactly her journey took place. She may have stayed employed at Jung’s shop while searching for new positions from there, or perhaps she was on the move the whole time. It is known, however, that she took her masters exam in 1940 while employed at Jung’s workshop in order to take his place while he was deployed in the war effort. In the paternalistic and war propagandistic style of the time, a different article by the Berliner Illustrierte states: “Young Berliner* becomes master* violinmaker. Capable girl heads the workshop while the owner is fighting in the theatre of war.” (M.M 1040)

Whatever the real nature of her employment between 1937 and 1940, she made a few very important acquaintances in that time – most notably, Simone Ferdinando Sacconi. According to the forward of the German translation of Sacconi’s book I “Segreti” di Stradivari, “she was [in her time in Cremona] allowed to experience the world’s most renowned violinmaker in casual conversations while drinking wine.” (Sacconi 1976, S. 19)

It would however, remain at this single encounter according to Adelmann, due to both the isolation of “cultural Germany” in the coming years and the additional work of heading the workshop while Curt Jung was away.

Jung was able to return to his shop after only one year of service as his son recalls. What happened to Adelmann after that is not clear from the available sources, as they tell conflicting stories. In 1961, Jung’s shop was moved to East Berlin, though at the time, Adelmann no longer worked there. Annette Otterstedt writes in her biography of Adelmann that she worked at the workshop of Georg Ullmann during the war (citing an article from 1940 as proof).Though the article actually states that she was still working at Jung’s shop. From the available sources it’s unclear when she started to work at Ullmann’s shop. In 1945, Adelmann tried to open her own shop but lost all her tools in an air raid, forcing her to start work again as an employee in different workshops. (D.M. 1957)

In 1956 she has, what she will later call, “the luckiest turn of events in my life”: employment as a restorer at the Musikinstrumenten-Museum SIMPK (at first as a freelancer*, but from 1960, as a fulltime employee). During this time, she completed two of her most important works.

In 1957 and 1960 the museum bought two bowed stringed instruments “of a strange and archaic look”. Olga was fascinated by these, with their unusual form and elaborate decorations. She started studying the instruments, documenting them meticulously and searching for similar instruments to compare them to. Her research brought her to different public and private collections in Europe, and above all to Switzerland. Piece-by-piece – or more precisely, instrument-by-instrument – and in continuous exchange with her colleagues worldwide, she reconstructed the history of these instruments and their makers. The results were published in her first publication, “Unsignierte Instrumente des Schweizer Geigenbauers Hans Krouchdaler. Zu einer vergessenen Geigenbauschule des 17. Jahrhunderts” (“Unsigned Instruments by the Swiss Violin Maker Hans Krouchdaler. On the Forgotten Violinmaking School of the 17th Century”) in the Jahrbuch des Staatlichen Instituts für Musikforschung from 1969. Just as she had hoped, the publication successfully brought to light other instruments and traces of that particular violinmaking tradition. (Adelmann 1997)

In 1969, she travelled to the USA (specifically New York), where Simone Ferdinando Sacconi had moved to and with whom she started exchange letters after the end of the war. She took this opportunity to renew their acquaintance. According to the forward of the German translation of Sacconi’s book, she visited him several times in his workshop at the Wurlizer Company, where he showed her his working methods and told her about the book he was writing, which would be published three years later.

![[Translate to English:] Geide der Alemanische Schule Violin with colourfull decorations on the top](/fileadmin/user_upload_sim/Bilder/Museum/Sammlung/Restaurierung/4519_Alemannische_Schule_Abb_4.jpg)

His approach was different to Möckel’s as he did not describe a new method to copy an historic instrument. Instead, he tried to reconstruct the historic construction method used by Stradivari, starting with the patterns and moulds from the Stradivari workshop and drawing conclusions from different markings he observed on original instruments during his time as a violin restorer.

In 1973, Olga Adelmann started to read Sacconi’s newly-published book (in the original Italian). Since her language skills where not up to the task of following “the complicated and precise explanations of the finest details”, she began to systematically translate the book. Although this was originally only for her own benefit, she later concluded that it could be valuable to have an official translation. For this project, her contact with other colleagues worldwide was of great help – in particular, Prof. Vinicio Gai, someone she knew “from the time when [she] was in Florence after the great flood of the 4th of November to restore instruments damaged by the event” (Sacconi 1976). Little can be found about this period in her life from the sources so far.

A recent finding in an office brought to light a folder containing letters exchanged between Adelmann and Sacconi, and later his wife Teresita. A letter of particular interest is to Adelmann by an American lawyer that managed the estate of Sacconi after his death in 1973. It is a reply regarding her intentions to translate the book. The lawyer orders Adelmann to stop any efforts to translate the book as the copyright and the right to any translation is retained by the heirs. How the matter was resolved is unknown but in 1976, the German translation by Adelmann with a forward by her is published, being the first official translation of this book. The English version was eventually published in 1979.

The importance of this book for the modern violinmaking craft cannot be understated. Today, almost every violinmaker knows the book and the name Simon Ferdinando Sacconi. But it is the translators and especially Olga Adelmann that made that possible.

This short intermezzo, however, did not deter her from the project that secured her place in violinmaking history. The publication of her article in the Jahrbuch des Staatlichen Instituts für Musikforschung in 1969 successfully brought to light other instruments and archival documents. In 1990, fourteen years after her retirement, she published her book Die Alemannische Schule. Archaischer Geigenbau im 17. Jahrhundert im südlichen Schwarzwald und der Schweiz (The Alemanic School. Archaic Violin Making in the 17th Century in the Southern Black Forest and Switzerland). All in all, Adelmann found, investigated, documented and catalogued twenty-one objects. In doing so, she not only identified and located the individual violinmakers but also meticulously analysed their style and construction methods. Her training as a violinmaker was a particular asset as it allowed her to replicate the methods employed by these forgotten masters to make a copy in their style. The Musikinstrumenten-Museum thus not only owns an interesting collection of these rare historic instruments but also the beautiful copy made by Olga Adelmann herself.

In 1996, the number of identified instruments went from twenty-one to thirty-three, which made it necessary to do a second edition of her book. In collaboration with her colleagues from the Staatlichen Institut für Musikforschung, they revised the whole book, adding new chapters and getting rid of the word “archaic” from the title. (Adelmann 1997)

Adelmann’s book was a breath of fresh air. Instead of focusing on Antonio Stradivari or other exponents of the Cremonese school, she shows that other violinmaking traditions are also important in their own right, despite (or perhaps due to) not following the aesthetic rules and working methods of the Cremonese masters.

The collection of the Musikinstrumenten-Museum SIMPK holds many items that document the life and work of Olga Adelmann: hand-written notes, documents, small objects and even entire instruments. Every day, one encounters something that she left behind. But the research about her life is scarce. Many questions remain unanswered and her importance for the modern violinmaking community is often forgotten.

References

(D.M.) (1957): Zauberin der Töne. Von der Werkstatt in die Instrumentensammlung des Schlosses Charlottenburg. In: Telegraf 1957, 20.03.1957.

(M.M) (XX.XX.1940): Junge Berlinerin wurde erste Geigenbau=Meisterin. Tüchtiges Mädchen führt die Werkstatt, während der Besitzer im Felde ist. In: Berliner illustrierte Nachtausgabe 1940, XX.XX.1940.

Adelmann, Olga (1997): Die Alemannische Schule. Geigenbau des 17. Jahrhunderts im südlichen Schwarzwald und in der Schweiz. Unter Mitarbeit von Olga Adelmann und Anette Otterstedt. 2. Aufl. Berlin: Staatliches Institut für Musikforschung.

Möckel, Otto (1967): Die Kunst des Geigenbaues. mit 150 Abbildungen und 33 Tafeln. Überarbeitete Ausgabe. Unter Mitarbeit von Fritz Winckel. 3. Aufl. Hamburg: Verlag Handwerk und Technik.

Otterstedt, Anette ((Datum unbekannt)): Olga Adelmann. FemBio Frauen-Biographieforschung e.V. Online verfügbar unter www.fembio.org/biographie.php/frau/biographie/olga-adelmann/, zuletzt geprüft am 30.06.2021.

Sacconi, Simone Ferdinando (1976): Die 'Geheimnisse' Stradivaris. deutsche Übersetzung: Olga Adelmann. Unter Mitarbeit von Simone Ferdinando Sacconi und Olga Adelmann. 1. Aufl. Frankfurt am Main: Verlag das Musikinstrument.

Schumann, Walter (1938): Olli, die Berliner Geigenbauerin. Es ist ein seltener Beruf für Frauen - Ihr großes Erlebnis: Wanderfahrt zu berühmten Geigen. In: Berliner illustrierte Nachtausgabe 1938, 20.01.1938, 1. Beiblatt.